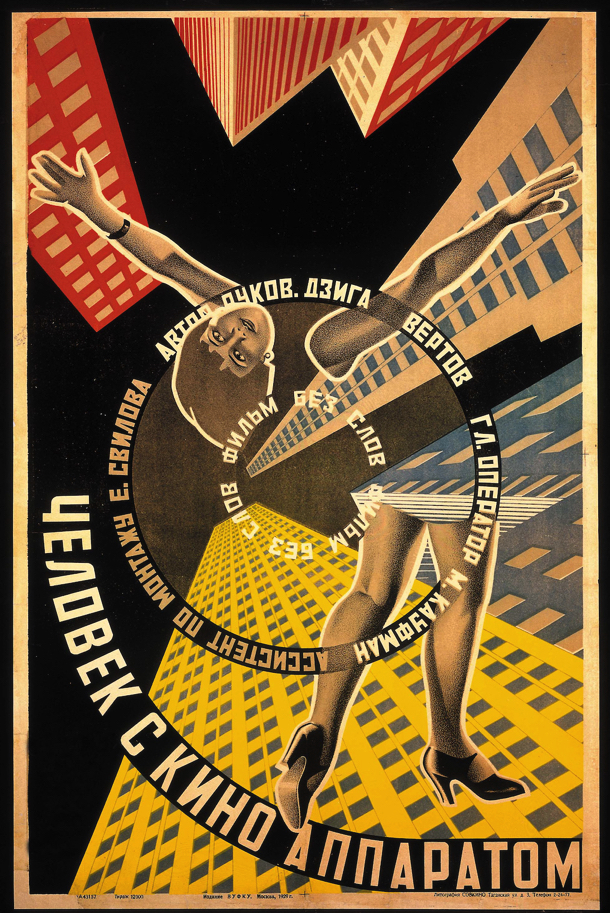

Of all of the cinematic pathblazers to emerge during the early years of the Soviet Union – Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Lev Kuleshov – Dziga Vertov (né Denis Arkadievitch Kaufguy, 1896–1954) was once essentially the most radical.

The placeas Eisenstein – as observed in that movie college standard Battlesend Potemkin – used montage editing to create new tactics of telling a story, Vertov dispensed with story altogether. He loathed fiction motion pictures. “The movie drama is the Opium of the people,” he wrote. “Down with Bourgeois fairy-tale eventualities…lengthy are living lifestyles as it’s!” He known as for the creation of a brand new roughly cinema freed from the counter-revolutionary baggage of Western films. A cinema that captured actual lifestyles.

On the startning of his masterpiece, A Man with a Movie Camera (1929) – which was once named in 2012 by means of Sight and Sound magazineazine because the eighth easiest film ever made – Vertov introduced actually what that roughly cinema would seem like:

This movie is an experiment in cinematic communication of actual occasions without the assistance of intertitles, without the assistance of a story, without the assistance of theatre. This experimalestal paintings goals at creating a truly international language of cinema according to its absolute separation from the language of theatre and literature.

Gleefully the use of bounce cuts, tremendousimpositions, break up monitors and each and every other trick in a filmmaker’s arsenal, Vertov, together with his editor (and spouse) Elizaveta Svilova, crafts a dizzying, impressionistic, propulsive portrait of the brand newly industrializing Soviet Union. The lengths to which Vertov is going to capture this “cinematic communication of actual occasions” are celebritytling: His camgeneration soars over towns and gazes up at boulevardautomobiles; it motion pictures machines chugging away or even data a girl giving beginning. “I’m eye. I’m a mechanical eye,” Vertov as soon as well-knownly wrote. “I, a gadget, am displaying you a global, the likes of which most effective I will be able to see.”

But Vertov’s stroke of genius was once to reveal all the artifice of moviemaking withwithin the film itself. In A Guy with a Film Camgeneration, Vertov shoots pictures of his camgenerationmales shooting pictures. There’s a recurring shot of an eye fixed celebritying thru a lens. We see photographs from earlier within the film getting edited into the movie. This type of cinematic self-reflexivity was once a long time forward of its time, influencing such long term experimalestal moviemakers as Chris Marker, Stan Brakhage and especially Jean-Luc Godard who in 1968 shaped a radical moviemaking collective known as The Dziga Vertov Group.

A Guy with a Film Camgeneration is nothing wanting exhilarating. Test it out above.

Word: An earlier version of this put up gave the impression on our website in November 2014.

Jonathan Crow is a author and moviemaker whose paintings has gave the impression in Yahoo!, The Hollywooden Reporter, and other publications.

Related Content:

Watch Dziga Vertov’s Soviet Toys: The First Soviet Animated Film Ever (1924)

8 Loose Movies by means of Dziga Vertov, Creator of Soviet Avant-Garde Documentumalestaries

Listen Dziga Vertov’s Revolutionary Experiments in Sound: From His Radio Widecasts to His First Sound Movie

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based author and moviemaker whose paintings has gave the impression in Yahoo!, The Hollywooden Reporter, and other publications. You’ll be able to follow him at @jonccrow.