Banks were given stuck “chasing yield” and took large losses when the Federal Reserve dramatically hiked rates of interest to combat inflation. The ones losses are nonetheless striking round, and a number of other mavens instructed Fortune many core problems from the 2023 banking disaster pose a persevered risk to the device if financial stipulations go to pot.

Simply over two years after the cave in of Silicon Valley Financial institution and First Republic, banks are nonetheless taking large losses due to prime rates of interest. That’s reason for main worry, a number of mavens instructed Fortune, particularly if President Donald Trump’s price lists result in the scary aggregate of “stagflation,” or emerging inflation coupled with slowing enlargement, hanging additional power on lenders.

U.S. banks held $482.4 billion in overall unrealized losses on securities investments on the finish of 2024, according to Federal Deposit Insurance coverage Company information, an building up of $118 billion, or 32.5%, from the former quarter. That quantity had risen to $515 billion when SVB fell sufferer to a financial institution run in March 2023 and peaked at $684 billion later that yr. Knowledge for the primary quarter of 2025 is anticipated later this week, however April’s spike in bond yields method any reprieve within the first 3 months of the yr was once most probably short-lived.

Those unrealized losses don’t display up on a financial institution’s source of revenue observation until the belongings are bought, however they constitute a looming risk to liquidity if depositors get spooked, mentioned Rebellion Cole, a finance professor at Florida Atlantic College who labored for a decade within the Federal Reserve Device.

“All it takes is one dangerous information tale about any of those banks, and we will have any other banking disaster like we had in March of [2023],” Cole, who has served as a different adviser to the World Financial Fund and Global Financial institution, instructed Fortune. “I’m amazed we haven’t had one since then.”

View this interactive chart on Fortune.com

There’s a very easy reason behind the chart above: When long-term rates of interest spike, the price of belongings like in a similar fashion long-dated U.S. debt or residential mortgage-backed securities declines.

Financial institution losses necessarily had been fluctuating with the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield, Cole mentioned, which has been on a wild experience in 2025 amid the Trump management’s chaotic tariff rollout. It these days sits above 4.5%, drawing near its prime within the fourth quarter.

At that stage, the banking device begins “seeing critical issues,” Amit Seru, a finance professor on the Stanford Graduate Faculty of Trade, mentioned in an e-mail observation to Fortune.

“It turns into rather dangerous at 5%,” added Seru, a senior fellow on the college’s Hoover Establishment, a conservative-leaning suppose tank.

Cole mentioned that will equate to kind of $600 billion to $700 billion in unrealized funding losses.

Because the chart presentations, lots of the ones securities are designated as being “held-to-maturity.” Since they don’t seem to be meant to be bought, adjustments of their marketplace worth aren’t mirrored immediately at the banks’ monetary statements and are as an alternative disclosed in steadiness sheet notes.

Then again, if lenders are compelled to dump a few of the ones investments, Cole mentioned, then all the portfolio should be marked to marketplace. That suggests those technically liquid belongings transform, for the banks’ functions, precisely the other.

“It’s like a rock striking over the neck of the banks,” Cole mentioned.

In the meantime, losses on securities deemed “available-for-sale” are recorded at the monetary statements, however don’t hit income until belongings are bought. For Cole, the honour makes little distinction. The fast death of SVB, he famous, got here after the financial institution introduced it will take a $2 billion loss at the sale of available-for-sale securities.

“3 days later, they have been closed,” Cole mentioned.

Subsequent banking disaster simply wishes ‘one spark’

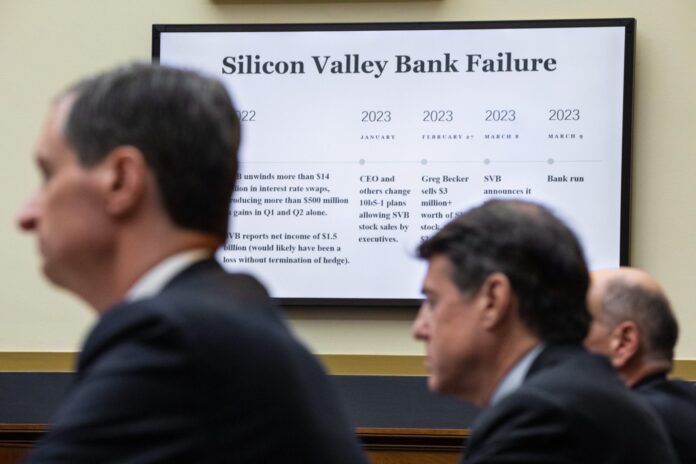

The failure of the tech business’s preeminent lender despatched shockwaves in the course of the monetary device and symbolized the folly of crudely “chasing yield.” When rates of interest went to 0 all the way through the COVID-19 pandemic, retaining a portion of deposits in momentary U.S. Treasury expenses supplied little go back.

Searching for slightly extra upside, banks appeared additional down the yield curve, pumping greater than $2 trillion into funding securities like long-term U.S. Treasuries (regarded as “risk-free” belongings, if held to complete reimbursement), mortgage-backed securities, and an identical belongings.

In 2022, the Fed first insisted it will simplest carry rates of interest reasonably to handle what it deemed to be “transitory” inflation. As an alternative, value enlargement surged to four-decade highs, and the central financial institution was once compelled to dramatically hike the federal budget price from kind of 0% in March 2022 to greater than 4.5% a yr later.

SVB, which had invested greater than 90% of its held-to-maturity portfolio in mortgage-backed securities, municipal bonds, and Treasuries with maturities of greater than 10 years, changed into the second-largest financial institution to fail in U.S. historical past. Not up to two months later, First Republic would overtake SVB on that checklist.

In spite of Fed intervention to make uninsured depositors entire and the acquisitions of each banks, the scars of the disaster and its ripple results nonetheless linger.

SVB’s fragility snuck up on regulators. They’ve since transform a lot more attuned to issues associated with interest-rate threat and depositor flight, Seru mentioned. However lots of the core problems persist, he added, as capital necessities nonetheless in large part forget about unrealized losses on securities and loans, whilst hedging methods stay restricted throughout a lot of the banking device.

“So whilst we won’t see any other disaster precisely like SVB’s, the substances for rigidity are nonetheless provide—particularly if macroeconomic stipulations go to pot,” Seru wrote.

And so long as rates of interest stay prime, losses banks amassed all the way through the disaster are nonetheless striking round.

“In a stagflation state of affairs, the chance is that charges can be upper for longer and credit score losses will start to acquire, particularly for lenders to tech, enlargement, and [venture capital], the place debtors are characterised by way of having no income and coffee protection ratios,” Torsten Sløk, leader economist at non-public fairness large Apollo International Control, wrote in a notice Monday.

Cole, in the meantime, mentioned he sees further power coming from a looming disaster in industrial actual property, leaving banks an increasing number of susceptible if funding losses put them underneath power. He mentioned he’s particularly frightened about regional and super-regional banks with $10 billion to $200 billion in belongings, lots of that are public corporations with main publicity to depositors with holdings above the FDIC’s $250,000 prohibit for insurance coverage.

“They are able to’t meet a kind of runs if they have got any unrealized losses on their securities portfolio,” Cole mentioned. “Then they’ll must mark that to marketplace, and the regulators will shut them.”

In brief, banks face a “nightmare state of affairs” and are sitting on a “tinderbox.”

“And it’s simply going to take one spark,” Cole mentioned.

This tale was once in the beginning featured on Fortune.com